Col. Ruth Streeter: Pioneer for CAP, Marine Corps Women's Reserve

CAP recognizes Women's History Month with a profile of Col. Ruth Cheney Streeter. An earlier version of this article appeared in Air University's Wild Blue Yonder online journal..

Col. Frank Blazich

Director

Col. Louisa S. Morse Center for CAP History Col. Ruth Cheney Streeter’s role as a founding member of Civil Air Patrol was complemented in the military, where she served during World War II as the first director of the U.S. Marine Corps Women’s Reserve.

Col. Ruth Cheney Streeter’s role as a founding member of Civil Air Patrol was complemented in the military, where she served during World War II as the first director of the U.S. Marine Corps Women’s Reserve.

Streeter’s contributions to CAP actually predate the organization’s creation on Dec. 1, 1941. She was a founding member of the New Jersey Civil Air Defense Services – the immediate model for what became CAP.

Subsequently, during the war she served as the Marine Corps’ first female major, lieutenant colonel and colonel and built the foundation for the postwar role of women Marines.

Before commissioning as a major in the Marines on Feb. 13, 1943, Streeter was a 47-year-old married mother of four. A native of Massachusetts, she had married lawyer and banker Thomas W. Streeter in 1917 and graduated from Bryn Mawr College in 1918, president of her class.

Moving to her husband’s hometown of Morristown, New Jersey, in 1922, Streeter settled into the roles of wife and mother, raising three sons and a daughter. When the Great Depression struck, she began to engage in public relief for her community and state. Throughout the decade, she worked in public health and welfare, unemployment relief and assistance to the elderly in New Jersey “because those were the needs during that decade,” she later recalled.

During the 1930s she served on the New Jersey State Relief Council, New Jersey Commission of Inter-State Cooperation and the New Jersey Board of Children’s Guardians.

In 1940 she acted on her long interest in aviation and learned to fly, earning her private pilot’s certification. That same year, the director of New Jersey’s Department of Aviation, Gill Robb Wilson, wrote to the chairman of the newly established New Jersey Defense Council about employing civilian aviation for national defense purposes.

The following year in May, Streeter became the only female member of the New Jersey Defense Council’s Committee on Aviation. The next month, the council approved Wilson’s plan to launch the Civil Air Defense Services’ New Jersey Wing to organize the state’s civilian aviation resources for effective cooperation with military and civilian defense forces.

Streeter was one of the new wing’s first members. By late summer she was 1st Lt. Streeter, A Flight, 2nd North Jersey Squadron of the CADS, flying and training with the wing’s 600 members and some 157 privately owned aircraft, including her own.

When CAP stood up as the nation plunged into war in December 1941, members of the New Jersey Wing of CADS began to work with and transition into CAP, including Streeter, eager to do her part of the war effort. She received CAP identification number 2-2-18, marking her as the 18th member of CAP from New Jersey.

When CAP stood up as the nation plunged into war in December 1941, members of the New Jersey Wing of CADS began to work with and transition into CAP, including Streeter, eager to do her part of the war effort. She received CAP identification number 2-2-18, marking her as the 18th member of CAP from New Jersey.

In January 1942 as adjutant of the Metropolitan Group (later Group 221) of CAP’s New Jersey Wing, she wrote to Maj. Ge. John F. Curry, CAP national commander, and his executive officer, Earle L. Johnson, explaining how civilian pilots received “an enormous ‘lift’ to feel that the heads of the Civil Air Patrol are really keen and on the job.”

She also detailed an idea for using CAP pilots to help ferry the simpler models of military trainer aircraft so military pilots could be freed for more important duty. Streeter earned her commercial pilot’s certificate that April, and the following month she received orders to ferry an aircraft to the 1st Task Force coastal patrol base at Atlantic City, New Jersey, for antisubmarine duty.

Yet while her personal aircraft flew antisubmarine patrol missions, Streeter, as a woman, could not. Instead, she found herself serving as a group adjutant inland doing “all the dirty work.” Frustrated but determined, she continued to fly and hone her skills, keen on joining the newly formed Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron.

At 47, however, she was 12 years past the age limit. After the squadron rejected her four times, Streeter met with Jackie Cochran to attempt to join her Women’s Flying Training Detachment. Cochrane gave Streeter her fifth rejection.

With two sons in the Navy and one in the Army, Streeter next attempted to join the Navy’s Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service in January 1943. When she asked if she could fly in the Navy, she was informed she could be a ground instructor instead. Streeter chose to walk out of the recruiting office.

Mere weeks later, she instead found herself being interviewed by the commandant of the Marine Corps, Lt. Gen. Thomas Holcomb, about becoming the inaugural Marine Corps Women’s Reserve director.

about becoming the inaugural Marine Corps Women’s Reserve director.

The Women’s Reserve intended to use women in noncombatant billets to release men for essential combat duty. Holcomb found in Streeter a qualified leader –, in his words, “somebody in charge in whom I’ve got complete confidence.”

On Jan. 29, 1943, Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox administered Streeter’s enlistment oath into the Marine Corps. She held a paying job for the first time in her life. She now held responsibility for recruiting, training and administration for the new female Marines.

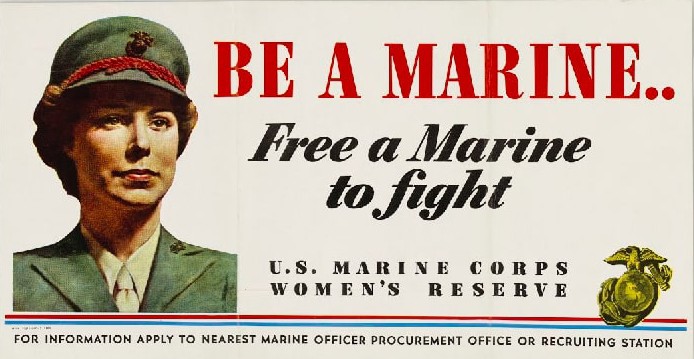

Although the Marine Corps was the last service branch to include women, Streeter wasted no time recruiting and speaking enthusiastically for the new organization to help “free a man to fight.” She was promoted to lieutenant colonel in November 1943 and colonel in February 1944.

By June 1 the Women’s Reserve had reached its authorized strength of 18,000 (831 officers, 17,714 enlisted total).

Streeter worked hard to obtain opportunities for women Marines to serve in roles other than clerical and administrative postings. By war’s end, women had attended about 30 specialist schools. Eventually. women Marines performed over 150 different duties nationwide and in Hawaii.

With aviation still close to Streeter’s heart, fully one-third of the reservists served in aviation technical fields. So great was the Reserve’s contribution in releasing men for combat assignments that the 6th Marine Division stood up and saw action at the Battle of Okinawa.

On Dec. 7, 1945, Streeter resigned her commission to return home to Morristown. On Feb. 4, 1946, Lt. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, commandant of the Marine Corps, awarded her the Legion of Merit, the highest award received by any female Marine during World War II. Her award citation proclaimed:

Under her inspiring leadership, the organization expanded to include approximately 19,000 women at the peak of the Marine Corps war program. A brilliant organizer and administrator, Colonel Streeter demonstrated a keen understanding of the abilities of women and of the tasks suited to them and, by her tact in fitting women into a military organization succeeded in directing the efforts of the women of the reserve into channels of the greatest usefulness to the Marine Corps and to the country, thereby contributing to the successful persecution of the war.

Through her dedication to her community and devoted patriotism to the nation, Streeter will forever remain a pioneering heroine to the Marine Corps and a model volunteer to all CAP members